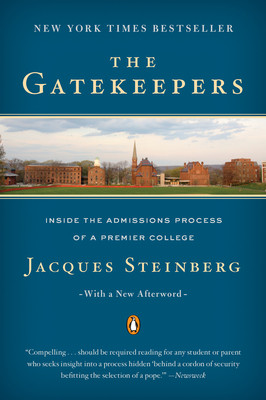

First published a decade ago, Jacques Steinberg’s book “The Gatekeepers” still offers a revealing window into how the college admissions process really works

First published a decade ago, Jacques Steinberg’s book “The Gatekeepers” still offers a revealing window into how the college admissions process really works

Every fall, as almost three quarters of American high school seniors prepare to apply to college, a new crop of teenagers and their parents wonder: who gets into the top schools and why? As anyone involved can tell you, it’s not based only on grades and test scores. Those are just two of many factors, some quite mysterious. In fact, how admissions offices at the most competitive colleges weigh those factors and make their decisions has long been a closely guarded secret. Oh, to be a fly on one of those ivy-covered walls!

A little over a decade ago, New York Times education writer Jacques Steinberg convinced Wesleyan University to let him be that fly. At the time, Wesleyan was a well-respected and up-and-coming school profiting from the rapidly multiplying number of college applicants in this country. As Steinberg describes it, the pyramid of elite colleges worked like a tower of champagne glasses, with applicants who didn’t quite make it into the Ivy League spilling down into the next tier of schools, which included Bates, Bowdoin, Colby, Middlebury, Williams, Amherst, Swarthmore and Wesleyan.

If you’re concerned with quality education, that’s a simplistic way to think about any of these schools, each of which offers an excellent education and has unique qualities of its own. But if you’re tracking admissions statistics and developing marketing strategies, the image of a champagne pyramid makes perfect sense.

Certainly it fits in with the numerically obsessed rankings compiled by U.S. News and World Report. Throughout the last decade, that single metric was a force that dominated and—some would argue—warped college admissions policies. The rankings’ disturbing influence is one of the themes of “The Gatekeepers.”

In 1999 and 2000 Steinberg spent nearly a year sitting in on meetings at Wesleyan and trailing admissions officer Ralph Figueroa as he traveled to California and New Mexico to visit high schools and meet prospective students. We hear how Wesleyan’s admissions staff read students’ applications—often putting in 12-hour days to keep up with the onslaught of paperwork—coded and graded each one, argued with their colleagues over each candidate’s merits and finally voted on each acceptance.

By taking readers into admissions office meetings, Steinberg lets us understand how most competitive colleges evaluate applicants; how they “read” each student’s files, grades and scores. Figueroa, a Mexican-American from California, explains why minority students from disadvantaged backgrounds are not required to have the same grades and test scores as more affluent students. And he makes the case for diversity, which enriches not only minority students, but everyone on campus.

Junk science

Figueroa laments the influence of the U.S. News & World Report rankings, which turn the entire admissions process into a giant numbers game. Worst of all, they essentially reward colleges for soliciting and then rejecting ever-greater numbers of applicants. That creates impressively low acceptance rates, suggesting that a school is highly desirable and very selective.

As bad as the situation was when Steinberg first researched his book in 2000, it has become more extreme in the intervening dozen years. In the updated 2012 edition, Steinberg points out that Wesleyan received 10,033 applications for its 2011 freshman class, a 43% increase over the number a decade earlier.

Of course, Ralph Figueroa is neither the first nor the last to attack the “junk science” of college ratings. But Steinberg’s insider observations point out some of the peculiar ironies the ratings system entails. In order to keep a college’s average SAT scores high, its admissions department must accept a super-achieving student for every lower-scoring, disadvantaged student.

The fact that SAT and ACT scores may not accurately reflect a student’s intelligence or academic abilities is a question Steinberg barely broaches. What’s clear is that, as long as Wesleyan and other schools agree to participate in the rankings, they will be beholden to SAT scores and other superficial measurements.

Steinberg describes how admissions officers favor star athletes, children of alumni and other special groups by assigning codes to their files that boost their chance of admission—sometimes by close to 50%. Then there’s the fact—no longer an “insider” secret—that applying to a college for early admission in November greatly increases a student’s chance of success. By the end of the 1990s, Steinberg tells us, “Some colleges, including Wesleyan, were admitting as much as 40% of the following year’s freshman class before most students had even applied.”

It might be comforting to think the admissions process at Wesleyan is somehow anomalous. But Steinberg assures us it isn’t. He chose the school for the similarities it shared with others on the “second tier” of the champagne pyramid, to say nothing of the first, and many other experts have backed his conclusions.

Following the applicants

Besides trailing Figueroa in his pursuit of prospective students, Steinberg follows six Wesleyan applicants to get a picture of the process from their side. This group includes Becca and Julianna, two girls from the prestigious Los Angeles prep school Harvard-Westlake; Tiffany, an Asian-American from a highly-ranked public school in Silicon Valley; Jordan, an ambitious public school boy from Staten Island; Aggie, a Dominican Prep-for-Prep student, and Mizigi, a film buff whom Figueroa recruits from the small Native American Preparatory School in New Mexico.

Of this small group, three end up receiving acceptances from Wesleyan, two are wait-listed and one is rejected. But that, of course, isn’t the end of the story. It is then up to the high school students to make their own decisions. Steinberg follows all six of them through the entire process. In admissions parlance, the two who end up at Wesleyan are termed “the yield.”

Questions about this article? Email us or leave a comment below.