The McIntire School of Commerce at the University of Virginia was long one of the few two-year undergraduate business programs in the United States

At elite undergraduate business schools across the country, employers routinely come to campus as early as students’ sophomore year to interview them for the sought-after summer internship following their junior year. But how can a business school support students if they don’t even matriculate until their junior year of college?

That was the position the University of Virginia McIntire School of Commerce found itself in over the last few years. The recruiting calendar had accelerated, but McIntire was stuck in a decades-old model: Students could only apply to McIntire’s undergraduate business program midway through their sophomore year. In that crucial recruitment window, the school could support future students only in an ad-hoc, patchwork fashion, as they weren’t even officially McIntire students when recruiting started.

“Employers had to come and identify students on their own and then our students had to compete for internship roles without very much of our involvement,” says Roger Martin, director of Mcintire’s undergraduate program. “That wasn’t good for either of us because it doesn’t let us help students put their best foot forward and doesn’t let students win those opportunities at the rate that they wanted.”

END OF AN ERA

McIntire Dean Nicole Thorne Jenkins: “It would have been challenging for us to have an additional year of undergraduate students and grow our minor without the space to house those classes”

The move from a two- to a three-year program will bring the 102-year-old school – which has stood out among its peers for the last few years as one of the last two-year business programs – in line with its peers. The faculty voted last spring to approve the new curriculum, and the class of 2028 will be the first class eligible to apply to the business school in late spring of their freshman year.

“This does mark the end of an era,” Martin says. “I think all business schools today are trying to enlarge the scope of what they cover. If you want to do that, you either have to take some things off the table or need to find the time to do that, which is what we have done.”

Indeed, the vast majority of elite undergraduate business programs now admit students either as freshman or sophomores and have three- or four-year programs, in which students come onto campus knowing they have a spot secured for them in the business school or will have a spot as long as they maintain a certain GPA, Martin says.

Mcintire was one of the last of the top undergraduate business schools clinging to that two-year model; just last summer, UC-Berkeley’s Haas School enrolled its first four-year class, also doing away with its two-year undergraduate business program.

CHANGES ABOUND AT THE SCHOOL

McIntire will move to a new model in the fall of 2025 in which students will apply to the school at the end of their freshman year, and start matriculating their sophomore year. The change makes it easier for the school to expand and enhance its course offerings, offer more tailored study abroad opportunities and allow students to have more flexibility with their coursework earlier in their college years, McIntire Dean Nicole Jenkins says.

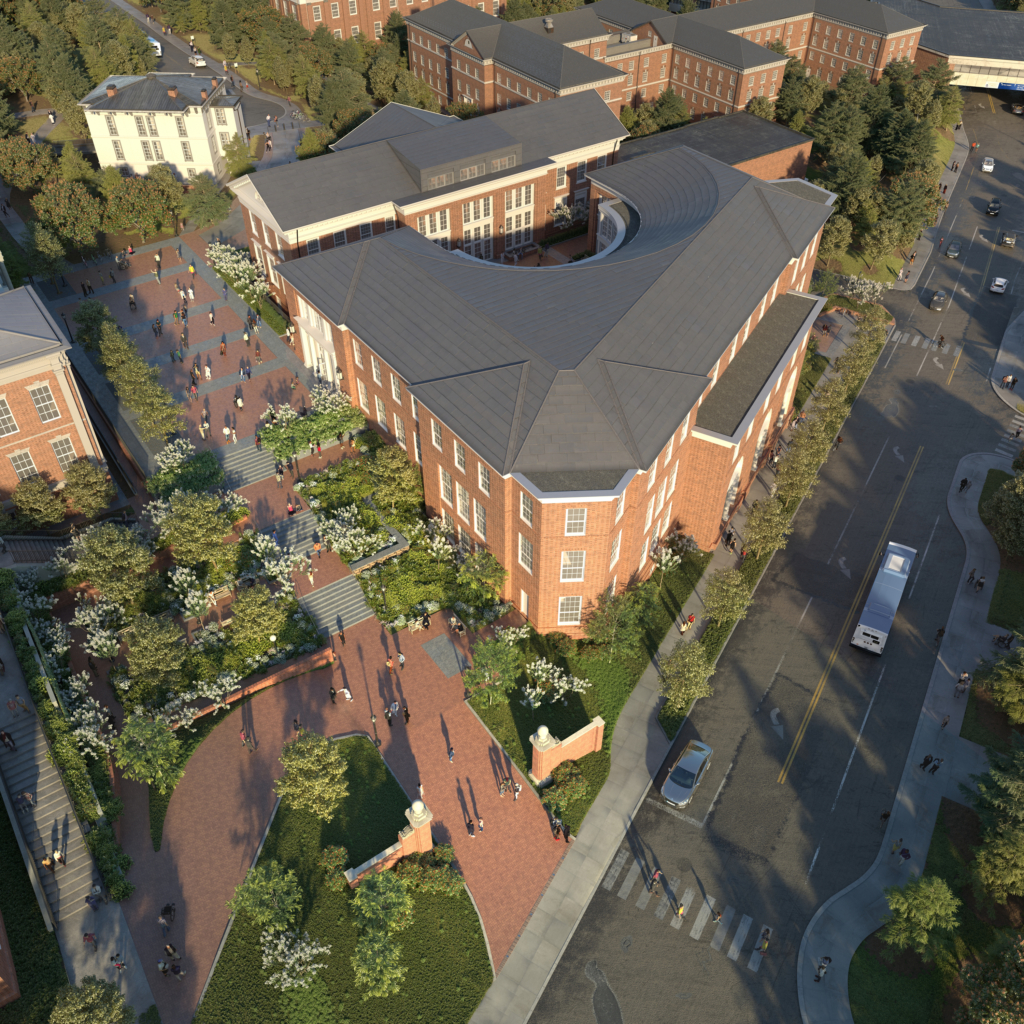

The move comes as the school is expanding its physical footprint at the university, with the soon-to-be completed addition of a new building on campus, Shumway Hall, and substantial renovations to an existing historical building the business school uses. This will add about 100,000-square-feet to the business school campus in 2025, and will give the school additional space for student services, study spaces and collaborative areas for students to work together, all of which will be necessary with the addition of an extra class to the school, says Jenkins.

“Having these two new buildings and this space gives us the opportunity to think differently about how we serve students, and is making these new programs possible for us,” Jenkins says. “It would have been challenging for us to have an additional year of undergraduate students and grow our minor without the space to house those classes.”

RECRUITING CYCLE OUT-OF-SYNC WITH COURSEWORK

Roger Martin: “I think all business schools today are trying to enlarge the scope of what they cover”

The process of changing McIntire’s current admissions model started in the fall of the 2021-22 academic year, a time when faculty and administrators took a step back and evaluated whether the school’s current program was still benefiting students, alumni and employers, says Jenkins, who joined the school as dean in July of 2020. Like others at the school, she was frustrated that sophomores had to take stopgap measures to make sure they didn’t fall behind with internship recruiting, such as competing for spots in a ‘Finance Academy” that some professors organized outside school hours to help them prepare for case-based interviews and employment treks.

“That was effective at closing the gap but there were some students who were falling through the cracks because the school couldn’t identify them,” she says.

The committee also realized it was time to rethink the lengthy list of prerequisite courses they had to take to even be considered for a seat in the McIntire School, including Introduction to Management Accounting, Applied Calculus and Introduction to Statistical Analysis. This year, more than 700 on-campus students applied for a seat at the McIntire School, about half of whom received an admissions offer, Jenkins says. That put the other 50% who didn’t get into McIntire at a disadvantage, because most of their coursework has been heavily quant-focused, making it hard for them to switch to other majors so late in the game, she says.

The changes the school is making will resolve some of those tensions.

“We are calling these some of the fall-out benefits of the changes we’re making,” she says. “Students will know between their first and second year if you are going to be in the Commerce School or not. If they don’t get in, they still have credit flexibility if they choose to become a history or dance major, whereas that was much harder before.”

LESS PREREQUISITES, LESS STRESS

Under the new model, students will only need to take an Introduction to Commerce and microeconomics course their freshman year as prerequisites to be considered for admission to Mcintire, Martin says.

The core curriculum, currently only taught in junior year at McIntire, will now be spread across their sophomore and junior years. The school’s well-known Integrated Core program — in which students get hands-on experience addressing real-world problems presented to them by companies — will still be introduced in the fall of their junior year.

In addition, the school is looking at enhancing the concentration, track and elective courses that students take their senior year, Martin says, and the faculty is currently in the process of developing new materials for those classes.

A NEW MINOR OPENS DOORS

The school has made the curricular change around the same time that they are introducing a new general business minor at the school, which underwent a pilot this academic year. Martin says he hopes that this new business minor will provide an avenue for students to stay engaged with the school even if they don’t get an admissions offer.

“We have more well-qualified students that we can admit, so this is a way for us to say to those who don’t get into the school that we have a great alternative for them,” he says.

Another benefit: Students will now have more time to pursue study abroad opportunities, and the school is working to develop new programs abroad they can pursue in the summer between their sophomore and junior years, Martin says.

STUDENTS RALLY BEHIND THE CHANGE

The changes at the school have been widely met with approval by the student body, says Commerce Council President Demond Morris, a senior at the school. This will will allow a more diverse pool of candidates to apply to the business school, as well as provide students at the business school with more support from the school on the internship front, he believes.

Sophomores have had to scramble to prepare for internships, whether vying for a coveted spot in the Finance Academy or asking for help from student campus groups who “have had to pick up the slack,” Morris says. The new admissions timeline will give students much-needed breathing room when it comes to figuring out their academic trajectories, he says, a boon to both students and the school.

“The current system can truly disenfranchise some of the students who want to go to Mcintire, apply and don’t get in because it is so late in the process. There are only so many avenues they can go if they don’t get into the program,” he says. “This will relieve some of the stress for students applying to the school, and I believe will also will encourage more students to apply to McIntire who might not have before.”

DON’T MISS: 2023’s Undergraduate Business Schools to Watch and 2022 Best & Brightest Business Major: Sambriddi Pandey, University of Virginia (McIntire)

Questions about this article? Email us or leave a comment below.