Judging by media reports that all of us have read, student debt is skyrocketing and has become a monumental burden to a generation of college graduates. But a new report on student debt by researchers at the Brookings Institution say the problem has been vastly exaggerated by those media-generated anecdotes of young people who can’t afford their own apartments or homes have to live with their parents in their 20s and 30s.

The truth, it turns out, is less headline worthy. In the Brookings report published June 24, 2014,, Beth Akers and Matthew Chingos analyze more than two decades of data on the financial well-being of American households and find that in reality, the impact of student loans may not be as dire as many commentators fear.

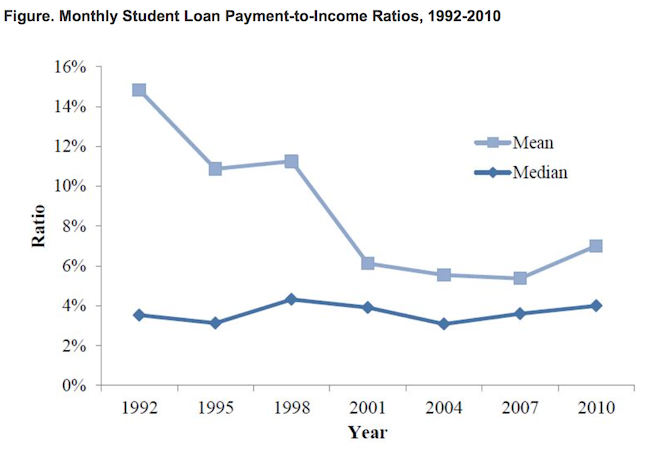

The Brookings study found, for example, that the monthly payment burden faced by student loan borrowers has stayed about the same or even lessened over the past two decades. The median borrower has consistently spent three to four percent of their monthly income on student loan payments since 1992, and the mean payment-to-income ratio has fallen significantly, from 15 to 7 percent. The average repayment term for student loans increased over this period, allowing borrowers to shoulder increased debt loads without larger monthly payments.

AVERAGE LIFETIME EARNINGS HAVE MORE THAN KEPT PACE WITH INCREASES IN DEBT LOADS

Akers and Chingos also discovered that increases in the average lifetime incomes of college-educated Americans have more than kept pace with increases in debt loads (see chart below). Between 1992 and 2010, the average household with student debt saw an increase of about $7,400 in annual income and $18,000 in total debt. In other words, the increase in earnings received over the course of 2.4 years would pay for the increase in debt incurred.

In fact, in 2011, college graduates between the ages of 23 and 25 earned $12,000 more per year, on average, than high school graduates in the same age group, and had employment rates 20 percentage points higher. Over the last 30 years, the increase in lifetime earnings associated with earning a bachelor’s degree has grown by 75 percent, while costs have grown by 50 percent

And finally, the researchers found that about one-quarter of the increase in student debt since 1989 can be directly attributed to Americans obtaining more education, especially graduate degrees. The average debt levels of borrowers with a graduate degree more than quadrupled, from just under $10,000 to more than $40,000. By comparison, the debt loads of those with only a bachelor’s degree increased by a smaller margin, from $6,000 to $16,000.

To be sure, student debt remains a significant issue for a lot of people. Over the last 20 years, inflation-adjusted tuition and fees have more than doubled at four-year public institutions, and have increased by more than 50 percent at private four-year and public two-year colleges. And students are borrowing more money to pay for education. Bachelor’s degree recipients in 2011-12 who took out student loans accumulated an average debt load of approximately $26,000 ($25,000 at public institutions, and $29,900 at private, nonprofit institutions). Current debt levels represent substantial increases over previous levels, with debt per borrower 20 percent higher in inflation-adjusted terms in 2011-12 than it was ten years prior .

In general, however, typical borrowers are no worse off now than they were a generation ago. Those media horror stories on graduates who struggle with high debt loads are not a part of a new and growing phenomenon. In fact, only two percent of young households owed more than $100,000 on their student loans in 2010, according to the Brookings study.

Questions about this article? Email us or leave a comment below.